Small World

The fantasy of uniqueness

By the time I was a mid-life wife and mother, I knew the Age of Exploration had long since long gone, and yet I still craved a sense of discovery—and of self-discovery—when I traveled. The word “trip” continued to have a ‘60’s ring. Over the years I’d come to realize that what I sought, now harder and harder to attain in this, the Age of Tourism, was an elusive state of mind that required perfect conditions. Timing was key: we had to arrive after the indoor plumbing was operational and just before the full-color brochures had gone out.

Traveling with my family to Belize in 1988, I still had high hopes. The jungle where we were headed seemed like the essence of the great beyond, both utterly foreign and rich in romantic associations. Through an agency specializing in equestrian travel[1], we’d arranged to stay at a small hotel in the rain forest bordering Guatemala and to ride out each day from a nearby ranch. At the time, we knew no one who’d been to the interior of the country, and we thought we were headed for a place, if not undiscovered by cartographers, at least undiscovered by promoters.

On the plane trip down I happened to be reading Barrie’s Peter Pan, so I noticed that from the air Belize  looked a lot like Neverland: “astonishing splashes of color here and there, and coral reefs and rakish-looking craft in the offing…and caves through which a river runs, and a hut fast going to decay…” I felt we were, like the Darling children, about to “break through” to a place I had known previously only in dreams and childhood fantasy, despite the fact that we were a mere two hours from Miami.

looked a lot like Neverland: “astonishing splashes of color here and there, and coral reefs and rakish-looking craft in the offing…and caves through which a river runs, and a hut fast going to decay…” I felt we were, like the Darling children, about to “break through” to a place I had known previously only in dreams and childhood fantasy, despite the fact that we were a mere two hours from Miami.

The illusion held. The airport of Belize had a charmingly make-shift quality and completely informal customs formalities. We were met by a tiny, wizened gentleman who smiled broadly and barely spoke. His car, a seriously dilapidated van, looked like it might have been driven down from the States twenty-five years earlier, during the first wave of hippy migration. Belize City, Belize’s only city, was a dusty, ramshackle place, a temporary solution that had gained permanency through tropical inertia. Skirting the edge of town, we began the 2 1/2-hour drive west to the mountains, traveling on one of the country’s three paved roads. For most of the trip, the landscape was flat, scrubby, and uneventful. Finally the vegetation thickened and we arrived in San Ignacio, a small jungle town where the only bridge over the Mascal River was located. It looked like a scene from a Graham Greene novel. Here we turned off onto a rough track and after another half hour arrived at our hotel.

The place was a hidden gem.  It was beautiful: a dozen conical thatched huts artfully set amid lush flora along the edge of a ravine, about as far from a Hilton operation as we could get. The almost private hideaway had been lovingly built by a globe-trotting couple who’d been so enchanted by the spot that they’d stopped looking further and had planted themselves. At our arrival, their three children, preteens like ours, descended on us with a clamorous welcome. New playmates were a rare treat for them but no less a thrill for our two—and for harried parents, is there a better definition of paradise? It seemed we might actually get a vacation along with our adventure. The five kids immediately fell into an enthusiastic game of tag that lasted well past the last rays of sunlight, while Michael and I luxuriated in being able to enjoy a pre-dinner drink unmolested. From the candle-lit, open-air dining room we looked out into the surrounding blackness, breathing in the perfume of invisible flowers and listening to the sonorous concert of a hidden army of frogs.

It was beautiful: a dozen conical thatched huts artfully set amid lush flora along the edge of a ravine, about as far from a Hilton operation as we could get. The almost private hideaway had been lovingly built by a globe-trotting couple who’d been so enchanted by the spot that they’d stopped looking further and had planted themselves. At our arrival, their three children, preteens like ours, descended on us with a clamorous welcome. New playmates were a rare treat for them but no less a thrill for our two—and for harried parents, is there a better definition of paradise? It seemed we might actually get a vacation along with our adventure. The five kids immediately fell into an enthusiastic game of tag that lasted well past the last rays of sunlight, while Michael and I luxuriated in being able to enjoy a pre-dinner drink unmolested. From the candle-lit, open-air dining room we looked out into the surrounding blackness, breathing in the perfume of invisible flowers and listening to the sonorous concert of a hidden army of frogs.

Everything about the place seemed perfect, not the least of which were our individual huts that had large screen-free windows opening onto the jungle and were lit only by shimmering gas lamps. Furniture was all hand-made, including some original, steeply inclined chairs of a native design. I would have expected Jared and Zoë, then 9 and 10, to be frightened by the strangeness and to put up a fight about sleeping in their own room, but the setting was strangely peaceful and they fell asleep instantly. Next door, Michael and I lay in our four-poster bed looking up into the cavernous thatched ceiling, wondering what kept the bugs and bats at bay and marveling at the voluptuousness of the place. I had a good track record for picking little, undiscovered hotels, but this time I’d outdone myself.

The sense of having cleverly chanced upon a strange, magical place was confirmed the next day—and from the first moment, when we were awakened by such raucous warbling that our conical room seemed like a human cage in an avian world. After breakfast we were given directions for the little daily trek we would make each day to avoid having to backtrack in the van to San Ignacio. Following a path down to the water’s edge alone, we boarded two waiting canoes, paddled to the opposite bank where we tied up to some protruding saplings, climbed the embankment, and hiked along a cut path for about 20 minutes. Even with two Gap-kids in tow, we felt like Stanley and Burton. Finally we emerged from the forest at the edge of a dusty back road where the van and its wizened driver were waiting to drive us another half-hour to the ranch. To get to this place we’d taken two planes, driven three hours into the interior, canoed across a river, and hiked through the jungle. We felt as though we were traveling to one of the most remote places on earth.

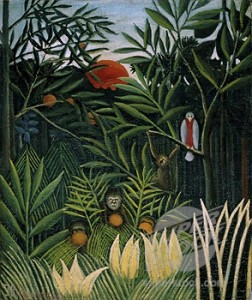

At the same time, the fact that I’d seen this landscape before in surrealist dream imagery and Disney cartoons gave everything a slightly unreal, deja-vu aura. Our guides turned out to be escapees from New Jersey—a former podiatrist and his tie-dye clad wife. And, why not? Whom else had I been expecting? We mounted up and rode off into a Rousseau painting

At the same time, the fact that I’d seen this landscape before in surrealist dream imagery and Disney cartoons gave everything a slightly unreal, deja-vu aura. Our guides turned out to be escapees from New Jersey—a former podiatrist and his tie-dye clad wife. And, why not? Whom else had I been expecting? We mounted up and rode off into a Rousseau painting  accompanied by giant, Blue Morphos butterflies. In this forest the plants I knew as potted clichés were luxuriant, towering trees; my florist’s most rare and expensive orchids and flowering bromeliads were everywhere, growing—well—wild.

accompanied by giant, Blue Morphos butterflies. In this forest the plants I knew as potted clichés were luxuriant, towering trees; my florist’s most rare and expensive orchids and flowering bromeliads were everywhere, growing—well—wild.

The first day offered a peak experience. After three hours of riding, we tied up the horses and hiked down about 60 feet to a beautiful waterfall. While we swam and climbed from pool to pool, our guides defrosted the iced tea and prepared lunch. Except for our Lycra bathing suits and the tortilla salad, it could have been a virgin moment in Eden, the original playground. Jared and Zoë, if given the choice, would have preferred to be at a resort hotel swimming in a “fantasy” pool, a pathetic imitation of this experience. But then they were still at an age that preferred processed cheese to the real thing.  I, however, was in seventh heaven, drifting along on the notion that this place existed out of time and for us alone.

I, however, was in seventh heaven, drifting along on the notion that this place existed out of time and for us alone.

Everyday, it seemed, offered a peak experience. And we responded by expecting nothing less. One day’s ride took us to a pond where we swam through some Tarzan vines and into a river cave for as far into the dark as our nerves would allow. Our guides told us that explorers had traced the river, traveling for miles and over twenty-four hours by canoe, to a ledge on which they’d found the skeletons of seven Mayan priests. Another day we traveled by van and a hand-operated car ferry to a nearby, riverside Mayan city where we had the ruins all to ourselves.

In the evenings, back at the hotel, we changed into swim suits and, along with the hotel-owners’ children, canoed up the river so that we could jump overboard and float down stream again: a mixed flotilla of boats, children, and dogs. Above us, giant iguanas climbed out on the overhanging branches of the guanagaste trees. The sounds of laughing falcons calling to one another across the water mixed with the laughter of the children. We might have been in a Kipling story or a Johnny Weissmuller film or a fauve painting. In fact, we were in a waking dream in which we had all the starring roles. We were having a great time, a fabulous time. But we also couldn’t wait to get home to tell our friends all about it.

On the last morning we left the hotel by the usual route, traversing the stream in canoes and hiking through the jungle. Now we knew enough about the rain forest to recognize some of what we were seeing. We passed enormous termite nests, elephant palms and strangler figs. Battalions of leaf-cutter ants marched in formation across our path. We were met by the van and driven to the ranch for the last time.

On the last morning we left the hotel by the usual route, traversing the stream in canoes and hiking through the jungle. Now we knew enough about the rain forest to recognize some of what we were seeing. We passed enormous termite nests, elephant palms and strangler figs. Battalions of leaf-cutter ants marched in formation across our path. We were met by the van and driven to the ranch for the last time.

On this day we were surprised to be joined by another family staying in a different hotel, one we’d had no idea even existed. In fact, I’d been thoroughly enjoying the notion that ours was the only one for miles, even the only one in the interior. The children stared at each other, astonished.

“You play second base for the Red Sox!”

“You’re the catcher for the Dodgers!”

Shrieking in unison, they recognized one another as competitors in the same neighborhood Little League. I was dumbstruck.  The fantasy we’d been savoring of the uniqueness of our experience might have survived the intrusion of strangers, but running smack into ourselves was more than it could take.

The fantasy we’d been savoring of the uniqueness of our experience might have survived the intrusion of strangers, but running smack into ourselves was more than it could take.

Nothing had changed, but everything seemed different. On that day we traveled to an underground cave with rooms of fabulous limestone formations illuminated only by the miners’ lights we wore on our heads and then stopped for lunch at another waterfall, one with myriad pools, some with little islands in them. But we did it all with the knowledge that the next Friday another group of wide-eyed visitors would be oohing over the same cave, aahing over the same waterfall. The experiences were wonderful, extraordinary in fact, but we knew for sure that it was Belize and not us that was extraordinary.

Once upon a time, the traveler moved West with the Night, Under a Sheltering Sky, When the Going was Good. She traveled under her own steam and took risks. Now the shiver of pleasure that accompanies the crossing of the threshold too often comes with the intimation that what we are enjoying was skillfully arranged for our pleasure. Today even a serious risk-taker can book quite challenging trips through a specialized agent. The rafting trip of traveling author, Tracy Johnston, was an adventure; she was ravaged by insects and nearly drowned more than once. But without the disasters, adventure travel is essentially adventure play. Could any voyage, however arduous, that is prearranged, all-inclusive and prepaid not be inherently passive at its core?

Still, like Peter Pan—that supreme egotist— I was still naive enough to demand the impossible. I wanted to come upon the waterfall myself, and I didn’t want to have to slash my way through the undergrowth to get to it. I wanted to indulge my reveries of exotic escape and without missing a meal or meeting up with a snake. I wanted to feel that I had traveled, not that I had been taken somewhere. And most essential of all—my visit to the outer reaches of beyond had to be the exact length of a school vacation.

site feed

site feed

A theory about the "small world" phenomenon + an amazing update on the essay story

As preamble, I need to mention that our female horseback riding guide, the podiatrist’s tie-dyed wife, complained at length about her ex for the ...

Does serendipity happen all the time?

An essay Mark Halprin wrote for the Home Section of the New York Times (Oct. 4, 2012) concerns some really quite amazing "good accidents" that ...

-

Why do children prefer a facsimile to the real thing?

Is it because it offers a sense of control over a frighteningly diverse world? Of course, it isn't only children who can't resist a simulacrum. ...

-

More on travel to Belize and by horse

Belize, a tiny, democratic, English-speaking country—the former British Honduras—remains an excellent vacation destination. While the interior offers rainforests, Mayan sites, bird-watching, river canoeing, and cave-exploring, ...

-

What is the imaginative lure of the jungle?

Henri Rousseau was a tax collector and self-taught painter who never left Paris and never saw a jungle, taking inspiration instead from Paris’ hothouse ...

-

related films

One of my favorite films of all time is all about this very subject: Lantana, 2001: an original, brilliant, Australian, mystery story whose underlying subject ...

related art

In the summer of 2011, The Museum of Art and Design in New York mounted an exhibit of small-world constructions by a number of ...

Bayard Fox March 1, 2012 at 11:17 am

This is a beautifully written story evoking an almost magical experience in the tropical forests of Belize with subterranean rivers, ancient Mayan ruins and children discovering the world’s wonders.