Bellicose Bambini

Italian feuds and sibling rivalry

The history of Italy is a gory tale of non-stop internecine fighting. If Disney had animated it, the tongue would be trying to devour the toe, the grommet to strangle the lace. To walk the otherwise charming old streets is to tread on centuries of dried blood, fratricidal blood. Other travelers may focus on Italy’s artistic glories, its religious traditions, its cultivation of sybaritic pleasure. But then they never traveled with my two warring teenagers.

When we left for Italy, the pair were at a stage where they could barely tolerate proximity to us or to one another. For years Zoë had been lording it over her younger brother, not infrequently making her point with a savage squeeze. Now Jared was surpassing her in height and strength. This was a tremendous moment, one he must have been imagining, like a prisoner his escape, for the better part of a decade. A showdown was still pending, but it would not take much to bring it on. Meanwhile, wherever I looked in new or old Italy I was greeted with reflections of our children’s fractious passions.

When we left for Italy, the pair were at a stage where they could barely tolerate proximity to us or to one another. For years Zoë had been lording it over her younger brother, not infrequently making her point with a savage squeeze. Now Jared was surpassing her in height and strength. This was a tremendous moment, one he must have been imagining, like a prisoner his escape, for the better part of a decade. A showdown was still pending, but it would not take much to bring it on. Meanwhile, wherever I looked in new or old Italy I was greeted with reflections of our children’s fractious passions.

* * * * *

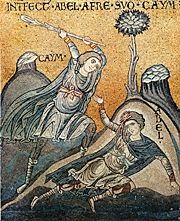

Our two-week trip began with a few days in Rome, founded, appropriately enough, with the spilling of brotherly blood. According to legend, the abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, found their way to the Palatine foothills where they were nursed by a loving wolf. Romulus drew a line in the dirt demarcating the sacred ground on which their new city was to be built. Remus, in jest, stepped over the line, for which his brother killed him. It’s an old story, a pagan Cain and Abel. And it struck a familiar cord: one sibling issues a hostile challenge masquerading as a tease, and the other, alert to the code, responds as though to a declaration of war. In the myth, things got out of hand—maybe it was the wolf milk.

Rome, the most sophisticated of cities, loves this tale of its  wild, bestial origins. The image of the lupine nursemaid suckling the two infants seemed to be everywhere, a curious counterpoint to the elegance of the passing parade. A handsome woman in black leather cruised by on a Vespa, a cigarillo dangling from her lips. Another, in a vast red cape, tossed a perfect auburn mane and stepped imperiously into oncoming traffic pushing her baby carriage. Everywhere businessmen hurried past, balancing overcoats on their shoulders while they spoke intensely into their cell phones. Even Jared and Zoë were impressed enough to cast off their dour adolescent expression for whole minutes at a time.

wild, bestial origins. The image of the lupine nursemaid suckling the two infants seemed to be everywhere, a curious counterpoint to the elegance of the passing parade. A handsome woman in black leather cruised by on a Vespa, a cigarillo dangling from her lips. Another, in a vast red cape, tossed a perfect auburn mane and stepped imperiously into oncoming traffic pushing her baby carriage. Everywhere businessmen hurried past, balancing overcoats on their shoulders while they spoke intensely into their cell phones. Even Jared and Zoë were impressed enough to cast off their dour adolescent expression for whole minutes at a time.

In the interstices between one sight and another, however, Jared would trip up Zoë, or she would knock off his cap, and they would be off, teasing and taunting, physical aggression only a nanosecond away. Food was the fix. As soon as passions bubbled, Michael and I would make a mad dash for a dolce or a chunk of pizza, often cut with gardening shears from a huge sheet and available at almost every turn. I carried a bar of Toblerone in my shoulder bag the way another mother might carry a bee sting kit.

The last night before leaving Rome we were introduced to the country’s tradition of national rivalry. At dinner with some Italian friends in a lively restaurant in the Campo dei Flori, the following joke was told to the assembled group:

A man opened a bottle washed up on the shore, releasing a genie who offered him two wishes.

“For my first wish,” said the man after some thought, “I would like Sicily to sink into the sea for a half hour.”

“And for your second wish?” asked the genie.

“I would like the same thing to happen one week later.”

“Of course, your wish is my command,” said the genie, “but may I ask why? If what you want is to rid yourself of the Sicilians, surely they would all have died the previous week.”

“Yes, but not the relatives — and they will all be coming to the funerals!”

The joke-teller was quick to disclaim all animosity for actual Sicilians, personally and generally, but in fact the division between Northern and Southern Italy is legendary and makes itself felt in all avenues of Italian life.

What looks at first like one unified country is essentially two loosely connected cultures: the prosperous, industrial North and the depressed, backward South. In fact, the two parts of the country have had distinctly different histories since their fortunes diverged at the end of the first millennium. The North saw the development of powerful, striving city-states while the South continued to be dominated and pillaged by a succession of foreign invaders. The local form of control was banditry, precursor to today’s Mafia.

Perhaps such continued hostility should not be surprising. Unified Italy is only 150 years old, barely out of its adolescence as nations go. But the main irritant is not Garibaldi’s scarcely contested annexation of the South but simple economic disparity. While the country as a whole has become one of the leading industrial nations of Europe—with, incidentally, the most successful businesses largely family owned and run—the average income in Southern Italy is barely half and unemployment almost double that of the North. Despite the fact that billions of dollars in the form of new roads, utilities and industries have been poured into the South, prosperity has not resulted. For over 50 years and at great expense, the government has been trying to build a highway from Naples to Calabria and from there a bridge to Sicily. The road, not to mention the bridge, remains on the drawing board. It’s a common Northern viewpoint that their hard-earned tax money is stolen and squandered by their Southern compatriots.

North and South Italy are like the two branches—one prosperous, one not—of a large, divisive family.  The rich cousins view their poor relations, for whom no hand-out or helping hand is ever enough, as having earned their apparent bad luck through laziness and lack of initiative. The disadvantaged cousins, for their part, resent their well off and smug relatives to whom, they feel, dumb good luck has brought an unearned birthright of wealth and opportunity. With hostilities fueled by the almost farcical excesses of Italy’s governmental bureaucracy, it’s a wonder the union holds. Paul Hofmann, a former chief of the New York Times Rome bureau, reported that in the early 1980’s when Mount Etna, the Sicilian volcano, was going through a period of eruptions, highway graffiti appeared on the overpasses near Venice: “Forza Etna!,” “Go Etna!”

The rich cousins view their poor relations, for whom no hand-out or helping hand is ever enough, as having earned their apparent bad luck through laziness and lack of initiative. The disadvantaged cousins, for their part, resent their well off and smug relatives to whom, they feel, dumb good luck has brought an unearned birthright of wealth and opportunity. With hostilities fueled by the almost farcical excesses of Italy’s governmental bureaucracy, it’s a wonder the union holds. Paul Hofmann, a former chief of the New York Times Rome bureau, reported that in the early 1980’s when Mount Etna, the Sicilian volcano, was going through a period of eruptions, highway graffiti appeared on the overpasses near Venice: “Forza Etna!,” “Go Etna!”

* * * * *

The South even lost in the competition for our family’s tourist dollars; our itinerary took us due north from Rome. With some difficulty we squeezed ourselves into the “medium sized” car we’d ordered. The luggage fit, but the newly attenuated limbs of our teenaged son and daughter just barely, leading to a fight over the opportunity of sitting behind me, since I could pull up my seat a few precious extra inches. Both quickly withdrew to the envelope of privacy provided by the deafening music of their personal CD players, but I knew our own Etna lay in wait. When fatigue or boredom reached an invisible threshold, my stashes of snacks were all that stood between an apparently pleasant family excursion and eruption.

In fact, minimizing cramping legs and crabby temperaments was the main organizing principle of our entire itinerary. I was as much a military strategist on a peacekeeping mission as I was a tour guide. We were on our way to Venice, taking three days to go less than 300 miles. On the first leg of our journey, we would be visiting fortified towns around Siena, but not Siena itself, since we would be returning there at the end of our trip for five days of horseback riding. Pisa was on the itinerary because of its high-profile landmark, familiar to our children from pizza box tops. Verona made the list because Romeo and Juliet is in the 9th grade curriculum. Florence was out: too much great art. For years our children loudly and jointly expressed their aversion to high culture. “No museums!” they shouted, the way pre-vegetarian generations had taken a stand against spinach. Perhaps I should have been grateful for this one area of agreement between them.

In the car, when the kids tuned out, I read aloud to Michael about the towns we were passing or about to visit. After the fall of Rome in 410 A.D., the history sounded like centuries of anarchy interspersed with periodic invasions. I had particular difficulty keeping track of the long-term quarrel between the Church and the Empire that, for most of the Middle Ages, divided Northern Italy into two teams: the Guelphs who supported the Pope in Rome and the Ghibellines who championed the Emperor.  Orvieto, 60 miles from Rome, was Guelph, but Arezzo, only 40 miles further north, was Ghibelline. Florence had citizens of both persuasions. First one group and then the other held the city, until finally the Guelphs created a republic that was itself undermined by an internal division into two contingents:Black Guelphs, loyal to the Pope and White Guelphs, opposed to the Pope. At this point even our guidebooks gave up and did not attempt to explain the differences between an anti-Pope White Guelph and a pro-Emperor Ghibelline. As far as I was concerned, Mercutio had it exactly right: “A plague ‘o both your houses.” Reading on, I learned that, in Florence at least, his curse was actually fulfilled in 1348 when the Black Death killed off more than half the population.

Orvieto, 60 miles from Rome, was Guelph, but Arezzo, only 40 miles further north, was Ghibelline. Florence had citizens of both persuasions. First one group and then the other held the city, until finally the Guelphs created a republic that was itself undermined by an internal division into two contingents:Black Guelphs, loyal to the Pope and White Guelphs, opposed to the Pope. At this point even our guidebooks gave up and did not attempt to explain the differences between an anti-Pope White Guelph and a pro-Emperor Ghibelline. As far as I was concerned, Mercutio had it exactly right: “A plague ‘o both your houses.” Reading on, I learned that, in Florence at least, his curse was actually fulfilled in 1348 when the Black Death killed off more than half the population.

Although the plague succeeded in dampening the fighting, it could not completely neutralize the intercity hostilities. They live on today. The Sienese and the Florentines both hate the Southerners, but they also passionately loath one another. Autumn mushroom hunting in the forests near Siena has become a favorite Florentine outing, but the Sienese have strong territorial feelings about their porcini. As a result, angry locals who identified Florentine invaders by the license plates on their parked cars slashed so many tires that the system of numbering plates had to be changed. Where else but in Italy would a feud dating from the Middle Ages finds its modern expression in a mushroom war?

We followed the Guelph-Ghibelline wars to Verona, the setting for the “canker’d hate” of the Capulets and the Montagues, whom the Veronese—pushing the historic basis of the story—claim were members of the two medieval political camps. Ever since the era of the European Grand Tour, the town has marketed itself as the site of Shakespeare’s play and particularly touted the supposed palace of the Capulets with Juliet’s famous balcony.  Although we were traveling during off-season, and Verona was not particularly crowded with visitors, the inner courtyard of Juliet’s house was standing room only. Five guides, in five different languages, instructed their unruly groups on the significance of the location. We could tell when each guide—on bended knee, one arm upstretched—got to the light-through-yonder-window line, their attempts to out-shout one another generating a babble of warring recitations.

Although we were traveling during off-season, and Verona was not particularly crowded with visitors, the inner courtyard of Juliet’s house was standing room only. Five guides, in five different languages, instructed their unruly groups on the significance of the location. We could tell when each guide—on bended knee, one arm upstretched—got to the light-through-yonder-window line, their attempts to out-shout one another generating a babble of warring recitations.

Happily Verona had more to offer in marvelous Roman ruins and Renaissance streets. Occasionally these were superimposed, one on another, as in the oval Piazza delle Erbe which occupies the footprint of the old forum without erasing its ghostly presence. Fortifying ourselves with gelati, we pushed on to the high point of our visit, literally and figuratively, the first-century Roman amphitheater. These days it’s the site of a famous summer opera festival, but the gruesome spectacles for which the building was constructed sprang unsolicited to mind. I tried to call up Rigoletto, but my brain was stuck on the Roman sports channel: mortal combat between two gladiators, two wild beasts, or a beast and a man.

* * * * *

Although it was less than an hour from Verona to Venice, having spent most of the day touring, we arrived on our last legs, primed for a blow up; but the drama of the floating city stunned us into silence. The surprise of having to drag our suitcases onto a vaporetto, the aquatic, Venetian public bus, short-circuited incendiary tempers. Even hauling our belongings over bridges and around sharp little corners only to miss our hotel—three times—seemed more ludicrous than exasperating.

For a while I thought that Venice itself, like Cinderella’s fairy godmother with her stardust-trailing magic wand, had returned us to an earlier time when, at least as I like to remember it, family life was less contentious. The irresistible charm of the city, whose architecture suggests nothing so much as a sugar candy fantasy in stone, seemed to inspire an unreal sweetness in our children. Normally slightly nervous in foreign cities, they seemed to feel safe among the promenading throngs and enjoyed walking around by themselves, exhilarated by the delectable foretaste of real independence. Rushing off to a concert one night after dinner, my husband and I anxiously left them to find their way home by vaporetto. This was a perfect opportunity for a little internecine nastiness: our fast-sprinting daughter could try to “lose” our son and give him a good scare. Instead, arriving back at the hotel, we found them companionably supine in their familiarly messy room, watching TV and munching the giant gummy worms they’d bought with their pooled lire, in a burst of friendly good cheer.

Three days in Venice passed without the usual cataclysm, but then it came, breaking all records, and just when we least expected it. It happened on Murano—a collection of small islands linked by bridges—across the Venice lagoon, where we had traveled, expressly for the children’s entertainment. Murano is the location of the famous glass works which were moved there in the 13th century to protect the city from the dangers of smelting furnaces. No churches or museums—just artisans forming glass into everything from tiny giraffes to enormous chandeliers. A child-friendly tourist site. I suppose, in hindsight I should have realized that our children had outgrown tiny giraffes. Five minutes of watching a bit of molten glass repeatedly worked into the same shape, and they were ready to leave. But the trip there had taken over an hour. The island must have something more to offer, Michael and I insisted.

Pushing on against the kids’ objections, I turned around to discover the two down on the sidewalk wrestling, Jared on top of Zoë, their faces contorted like gargoyles. I was horrified but afraid to step in. Two people brawling in public was bad; three could only be worse. The children were inches from the edge of the quay, and I could barely restrain myself from shrieking a warning, a sure way to get at least one pushed into the canal. “Do something,” I pleaded with Michael, and cravenly rushed around the next corner where I waited for the splash—which never came. Having gotten to the brink of murderous rage, they pulled themselves back. Rounding the corner, the two were still smoldering but dry and in one piece. With no restaurants or food shops to turn to, we beat a speedy retreat.

Later, I asked for an explanation but got only symmetrical glowers in response.  What was it about Jared that made Zoë so angry? “I don’t know… Everything!” What drove Jared so crazy—specifically? “I don’t know….Her face, her mouth, the way she chews!” The mere existence of the other was more than either could bear. They seemed to be gasping for breath, choked by invisible forces that had a stranglehold on them both.

What was it about Jared that made Zoë so angry? “I don’t know… Everything!” What drove Jared so crazy—specifically? “I don’t know….Her face, her mouth, the way she chews!” The mere existence of the other was more than either could bear. They seemed to be gasping for breath, choked by invisible forces that had a stranglehold on them both.

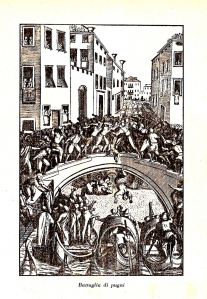

I was mortified that my children should be pulled down by such primitive animosity, but it turns out that they were following an old Venetian tradition, the battagliole, or the mock battles of the bridges. This phenomenon of late Renaissance Venice was a ritualized warring of workers and artisans for the honor of dominating certain bridges in the city. The battles were fought by two factions, the Castellani and the Nicolotti, descendants of the original two groups that migrated to Venice, one from the mainland and the other from the islands around the lagoon. As early as 800 A.D. there were stick battles between the two antagonistic groups.  More formalized battagliole began almost as soon as the city’s wooden bridges were rebuilt in stone, around 1500, and continued for two hundred years. The competitions, initially fought with pointed wooden poles, were later restricted to unarmed shoving and punching. The largest battles were prearranged and preceded by days of preparations, but fights could be set off spontaneously by the slightest provocation. In either case, squads of pugilists, fighting under a capo, followed a series of unwritten rules.

More formalized battagliole began almost as soon as the city’s wooden bridges were rebuilt in stone, around 1500, and continued for two hundred years. The competitions, initially fought with pointed wooden poles, were later restricted to unarmed shoving and punching. The largest battles were prearranged and preceded by days of preparations, but fights could be set off spontaneously by the slightest provocation. In either case, squads of pugilists, fighting under a capo, followed a series of unwritten rules.

Basically the battagliole were turf battles. Except for a few parts of the city like The Rialto or San Marco that were too public for either side to claim, the city was divided in two. Certain bridges became the natural focus of the tensions and the locus of the mass fistfights because they stood on factional boundaries and were large and strong enough to support the armies of fighters. Perfect stages for these public performances, they elevated the fighters and kept the crowds of onlookers at a safe distance. The battles could involve as many as 1000 combatants and 30,000 spectators, who cheered the fighting from the street, from boats, and from windows and rooftops. Though they were as much a form of festive competition as factional struggles, the fighting often resembled chaotic rioting, and many participants died or suffered serious maiming and injury. Henry III of France, watching a melee of some 600 armed artisans in 1574, declared the event “too small to be a war and too cruel to be a game.”

Why these battles remained popular in spite of their real dangers is a question that arose even then. To some onlookers it appeared insane. Normally rational artisans with families and livelihoods could go berserk, excited by the crowds and factional passions, the quest for glory, the wish to assert their individualism and independence. Venetians of the time explained the depth of passion by a farfetched reference to a mythic event of two hundred years earlier involving the brutal murder of a bishop over a question of taxation.  But whatever the source of the hostility, deconstructing animosity by searching for its origin is futile, as any parent of warring children knows, large and small, rationalize their entrenched hostility by tracing their anger back to a prehistory of original injury.

But whatever the source of the hostility, deconstructing animosity by searching for its origin is futile, as any parent of warring children knows, large and small, rationalize their entrenched hostility by tracing their anger back to a prehistory of original injury.

Eventually, however, the bridge battles came to an end. In 1705, a fire broke out in a nearby convent while a battle was deteriorating into a near riot, and, with no one free to fight the fire, the church was gutted. Perhaps such excesses convinced the majority of Venetians that the bridge battles had gone too far. Or perhaps it was the state’s loss of patience with them, or the decline in prestige and financial support that resulted when the elite’s interest shifted to the more refined pleasures of the Enlightenment. For the next hundred years, the factional energy of the battagliole was diverted to acrobatic contests involving the construction of human pyramids composed of seven or eight layers of men, 40 feet high. The regatta, rowing competitions which had been popular for centuries, were the final repositories for Venetian competitive passions and continue today, although now largely for the benefit of tourists.

* * * * *

Reeling from the mayhem of Murano, I looked forward to getting to the horseback-riding segment of our trip; we could use a change and a new mode of transport might be just the thing. On the other hand, I also knew that Siena happens to be the world capital of factionalism.

We had arranged to have the day to visit the city, meeting up with our host/guide for dinner. All the narrow winding streets, closed to automobiles, lead to the Campo, the fan shaped “square” which is the location of Siena’s famous summer horse race, the Palio. We visited the town hall with its rooms upon rooms of exuberant frescoes and the Duomo with its spectacular carved and inlaid narrative floors: textured carpets of marble. Jared and Zoë, however, were more interested in locating the 14th century preserved head of Saint Catherine on display in another church. We finally found the holy relic in a darkened gilt framed box, noseless but flesh toned, its expression more of horror than beatitude. The children gave it their most rapt attention.

In contrast to the saint, Vittorio, our charming Sienese host and guide, had a round, rosy, cherubic face and, surprising for an equestrian, a Falstaffian girth. Over dinner we plied him with questions about the Palio, surely the ultimate tourist event, with its 800-year-old processions in full medieval regalia, flags flying and drums beating. Yet it is not at all intended for tourists. Quite the reverse. If the Sienese had their druthers, strangers would be barred. So seriously is the Palio taken, so significant an event is it in the life of the Sienese, that citizens who have moved to other parts of Italy feel compelled to return for it each year. The obsession is even honored by the federal government that routinely grants passes to Sienese serving in the armed forces so they can return home for the race.

The city may be unified in its hostility to Florence, but within its walls it is divided into 17 wards (down from an original eighty), called contrade, whose historic alliances and rivalries go back hundreds of years. Each year, the competing wards—only ten, for safety’s sake—hire professional jockeys who are at once modern mercenaries and proxy warriors. The race, considered among the most dangerous in the world, is ridden bareback, three laps around the irregularly banked main square. The only whip allowed—with which the jockeys beat their horses and occasionally one another—looks like a four-foot long collapsed tube of cowhide and is actually made from a bull phallus. Tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars change hands in complex, secret, and underhanded payoffs. Anything goes and the dirty-dealing contributes substantially to the fun and excitement of the race.

That the origins of the ward alliances and animosities are only vaguely understood does not detract from their intensity and importance. Within the walls of the city, people describe themselves by their contrade membership: “I am of the Porcupine.” or “I am of the Wave.” In Lis Harris’s 1989 article on the Palio for the New Yorker, she writes that for many Sienese the ward “plays an emotional role more central even than the family,” which, for Italians, is saying a great deal.

As the day of the race approaches, hostilities increase with considerable taunting and singing of insulting, scatological songs. The race itself is over in a flash, but not before many horses stumble, sometimes falling and bringing nearby horses down with them. As the first horse crosses the finish line, with or without its jockey, its ward members explode in an exultant cry. The Palio may be many things: a celebration of cultural roots, a shared ritual that heightens the perception of being alive, an expression of the yearning for victory. Still, it is hard to avoid interpreting the event as, above all, a vehicle for arousing and venting primitive, rivalrous passions.

Vittorio, our horseman guide, was not Sienese, but his wife was. He was also decidedly not a Palio enthusiast and avoided, as much as he could, anything to do with the race. It seemed, however, to be inescapable. Even riding in the hills far outside the town, we saw signs of the race everywhere. We passed modest farms whose owners bred Palio horses, an expensive hobby since the immense profits from the race go exclusively to the jockey, not to the horse. We met a maker of whips. We rode past tracks constructed to reproduce the Campo where horses and jockeys could train, huge areas put aside merely for the pleasure and accrued honor of a more intimate association with the race. According to Vittorio what we saw was proof that the Sienese, his wife included, were all crazy.

I, however, was inclined to admire their ingenuity, particularly when I noticed that the riding absorbed the fractious tensions of our offspring pretty much the way the Palio seemed to do for the Sienese. It is generally held that the almost total absence of violent crime in Siena is due to the race’s ritualized channeling of primitive emotion. Venting and celebrating such passions in sport was an invention of the Enlightenment and a civilizing step forward for humanity. The week we rode was the most peaceful of the vacation.

* * * * *

The trip ended uneventfully, and Jared and Zoë, as far as I know, never again fell to blows. There may be, as for the end of the battagliole, more than one explanation. Perhaps the Battle of Murano convinced my son that he could dominate, thereby releasing him from the need to, while my daughter may have concluded that avoidance was the better part of valor. Perhaps they both felt they have crossed a threshold. A few months after the trip, Jared referred grimly to the Murano incident, “God Mom! We were actually rolling on the ground in public!”

Still, I continue to wonder why my children’s rivalry became so overheated. Were the dynamic forces of our family especially intense? Or was it simply the result of a personality clash of two young people who were constantly, involuntarily together?  Of the many significant roles they had come to play in one another’s lives, that of personal scapegoat, the convenient object of blame for every frustration, had for that period of time become the most useful. And their familiarity had led to the lack of inhibition that made physical aggression possible. They had been infants together. They could be primitive with one another when it would be unthinkable with others.

Of the many significant roles they had come to play in one another’s lives, that of personal scapegoat, the convenient object of blame for every frustration, had for that period of time become the most useful. And their familiarity had led to the lack of inhibition that made physical aggression possible. They had been infants together. They could be primitive with one another when it would be unthinkable with others.

As obsessively self-conscious, post-Freudian parents, Michael and I had been careful never to compare them, to always “celebrate their uniqueness,” to treat them equally. How naive to think we could have immunized them against rivalry. However much we pursued the ideal of fairness, complete equality was impossible. Our children knew that to get the red ball was to not get the blue one, to be the older was to not be the younger, to be a girl was to not be a boy. Although all their lives they would be competing with others for college placement, for jobs, for recognition of achievement, in their own minds they were vying principally with one another, all other contests a mere shadow of the original one. But it was also possible that their rivalry was about more than just competition for an imagined prize. Like the Castellani and Nicolotti they might have been pitting themselves against one another in their struggle to form personal identities. And then, like the ward members of Siena, their mutual animosity might have sprung less from ongoing injuries than from a tradition of hostility.

Sibling warfare may have waned in our house, but my preoccupation with the theme remains as strong as ever. The national division into two competing factions seems ubiquitous. The whole world seems fractured by murderous sibling animosities: The Israelis and the Palestinians, the Tutsis and the Hutus, the Serbs and Croats, the Chechens and Russians, the Sunnis and the Shiites, Red and Blue America. Two brothers who can only picture themselves as sitting face to face on a common seesaw, the rising fortunes of one necessarily at the other’s expense. Two groups who have more in common with one another than with any other group in the world nevertheless define themselves as polar opposites. Their differences, seen through the distorted lens of resentment and jealousy, appear to them greater than their common ground.

With only one language, race, and culture, Italy’s widespread factionalism is particularly curious. Perhaps it is related to the intensity of the Italian family, the source of exceptionally successful enterprises and personal achievement when all goes well, but of powerful feuds between or even within them, when something goes awry. In Italy, however, where daily life has been refined to a fine art, fractious passions are for the most part transformed with characteristic elegance and refinement. The Northerners and Southerners, the Sienese and Florentines, the contradaioli of the Tower and Goose despise one another. And yet today the Italians essentially manage their rivalries without resort to violence. In many cases they relish them. They have moved from armed battle to ritualized fistfights to horse racing: from war to sport. They have progressed from hating one another to loving to hate one another, a subtle but significant distinction. Cultural alchemists, the Italians transform even divisive rivalry into extravagant celebrations of human passion.

More

- related films

site feed

site feed

-

What are the preconditions of a blood feud?

On the right, Randolph McCoy, whose brother Harmon’s death was blamed on Jim Vance, the uncle of the man on the left, Devil Anse Hatfield. ...

Are nations driven by the same emotions that drive individuals?

How is it that nations seem to be driven by some of the same emotions that drive individuals? The notion of human beings operating on ...

-

Can twin studies help us understand sibling rivalry?

Why are some twins so close as to develop something approximating a private language (called idioglossia or cryptophasia) while others are connected only by ...

-

Related films

Shakespeare in Love, winner of the 1998 Best Picture Oscar and an irresistibly romantic and clever fantasy about the writing of Romeo and ...

Why is sibling rivalry such a rare subject in film and literature?

Sibling rivalry is one of the key life challenges for most people. According to a new book, "The Sibling Rivalry Effect," conflicts arise every 17 ...

-

How can parents thwart sibling rivalry?

Are there any new ideas about what parents can do to thwart sibling rivalry? For common sense thoughts on the subject see this reasoned link. ...

Are sibling influences greater than parental ones?

My son sent me a link to an NPR article on some research indicating that a younger sister is five times more likely to become ...