- Attached to the essay "Dark Chocolate"

related art

Posted May 17, 2011 9:13 pmIs the historic depiction of people according to racial category inherently demeaning?

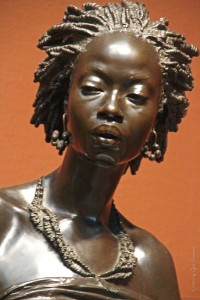

Today, when we appreciate the individual and abhor what we perceive as an attack on unique identity, such categorizing seems repugnant. But in times past, when encounters between ethnic groups were unusual, innocent fascination at human variety isn’t hard to imagine. Sebastian Smee, in an article in the Boston Globe, discusses a 19th century portrait bust by Charles Cordier of a Guadeloupe woman enslaved in Africa. It is a distinctive portrait but sculpted with great attention to ethnographic detail, not surprising since Cordier worked at Paris’ Natural History Museum, where he produced a series of ethnic portraits much appreciated by colonial rulers like Napoleon III and Queen Victoria. Though the sculpture is moving and life-like, Smee quotes Lionel Trilling’s caution against the tendency to move from making our fellow man “the object of enlightened interest…to the objects of our pity, then of our wisdom, ultimately of our coercion” (from”Manners, Morals, and the Novel”, in the Liberal Imagination). Is such a trajectory inescapable?

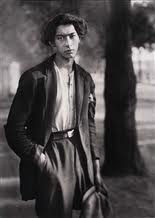

In the early 20th century, August Sander began to photograph a catalog of the German people according to profession or place in society, his “People of the 20th Century.” His 40,000 images in the series allowed the subjects to present themselves as they wished to be seen and are considered masterpieces of individual portraiture. Here his photo of a German gypsy:

In the early 20th century, August Sander began to photograph a catalog of the German people according to profession or place in society, his “People of the 20th Century.” His 40,000 images in the series allowed the subjects to present themselves as they wished to be seen and are considered masterpieces of individual portraiture. Here his photo of a German gypsy:

A year ago I traveled to South Omo, Ethiopia, an area said to be the last opportunity to see the pre-colonial Africa of our fantasies: a region of exotic traditions, untouched by time or Western influence—and on the cusp of irreversible change. Before our trip I worried about the voyeurism in traveling specifically to see tribal exoticism, but the people we met, whether wearing lip plates or body paint, were as curious about us as we were about them. What lessened my discomfort was the equality of our mutual interest, each of us amazed at the markedly different ways to be human. Perhaps if an African portrait of a colonialist could be exhibited next to the Cordier, it would lesson our discomfort with the sculpture as well.

share

site feed

site feed