previous

Related books

starting exploration

Thoughts and questions related to the essay “Edna’s List”

- Attached to the essay "Edna’s List"

Does an originial manuscript impart more than a digitized copy–or not?

Posted May 9, 2012 7:57 pm James Gleick (The Information: A History of Theory, a Flood) has written about books themselves as fetishized objects in a NY Times op-ed piece.

James Gleick (The Information: A History of Theory, a Flood) has written about books themselves as fetishized objects in a NY Times op-ed piece.

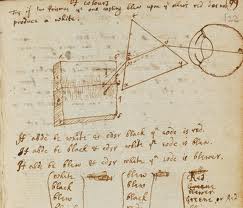

He describes the thrill of holding an original manuscript of Isaac Newton’s as, what he calls poetically, “a contact high.” But, more and more, books are digitized and made available quickly and easily to anyone with a computer and internet connection. Is this a wonderful advance? Apparently, not to everyone.

Gleick quotes an English historian, Tristram Hunt, who has written that universal access threatens to cheapen scholarship, “It is only with MS in hand that the real meaning of the text becomes apparent: its rhythms and cadences, the relationship of image to word, the passion of the argument or cold logic of the case.” Gleick sees this as “sentimentalism, and even fetishization. It’s related to the fancy that what one loves about books is the grain of the paper and the scent of the glue.” Perhaps. But I can also see how an author’s penmanship might reveal much about his character and frame of mind, even his passion—or lack thereof—for a particular argument.

Hunt’s elevation of the object reflects, according to Gleick, the notion that things are obtained more easily at the cost of their value. “If an amateur can be beamed to the top of Mount Everest, will the view be as magnificent as for someone who has accomplished the climb? Maybe not, because magnificence is subjective. But it’s the same view.” Here, I think, Gleick undoes his point. It’s not only magnificence that is subjective—but all experience. Newton’s notebook whether read on line or in hand may transmit the same information, but the experience of taking in that information will be different. It is not hard to imagine that the “contact high” of holding the original, of feeling more intimately connected to the author, may itself inspire insights that might otherwise not have occurred.

Gleick points out that the digital world “unlinks” the association of value and scarcity in informational relics. The original manuscript may have special worth for the antiquarian, but the ideas held within it are free to all. “An object like this—a talisman—is like the coffin at a funeral. It deserves to be honored, but the soul has moved on.” An odd analogy: isn’t it the body, not the coffin, that is honored? And what of those of us who see the idea of the soul itself as a sentimental fancy? Certainly, one’s actions and words, not one’s body, are the value and summary of a life, but why deny the potency of remains? Personal relics give survivors a palpable sense of the deceased, reveal something of the individual person, and help generate a feeling of closeness. Why should this not apply to authors from the past as well?

topics: culture

share

site feed

site feed