previous

Was the first list written to encourage travel or just put to this use?

starting exploration

Thoughts and questions related to the essay “Edna’s List”

- Attached to the essay "Edna’s List"

The difference between travel and tourism

Posted November 6, 2012 8:59 pmLots have been written on this question. One of my favorite explications of the difference is Paul Fussell’s essay “From Exploration to Travel to Tourism” in his book Abroad, published in 1980. Fussell has the history wrong, writing that “exploration belongs to the Renaissance, travel to the bourgeois age, tourism to our proletarian moment”—apparently, forgetting about the Greeks. Be that as it may, the essay is funny, snobbish and smart. Fussell reminisces about the romance and glamor of “transatlantic lovelies” and dreamed “of lolling at the rail unshaven in a dirty white linen suit on a crummy little ship” in the Orient, like a character from a Graham Greene novel. Essentially, he draws the line between opening oneself to some misadventure and being passive and protected. As for himself, he writes,”although I have been both traveler and tourist, it was as a traveler, not a tourist, that I once watched my wallet and passport slither down a Turkish toilet in Bodrum, and it was the arm of a traveler that reached deep, deep into the cloaca to retrieve them.” It’s interesting to reread Fussell today. He writes of being among the 200 million tourists traveling the globe each year. Today there are nearly a billion of us.

And there is still more to say on the travel v. tourism subject. A recent (7/8/12) essay in the NY Times by Ilan Stavans, a literature professor at Amherst, and Joshua Ellison, editor of the journal Habitus, looks upon travel as an essential human experience—from the expulsion from Eden on—of potentially epic significance. They write of the immigrant as “a traveler without a return ticket.” And they bemoan the prosaic nature of modern tourism but feel that though “we may never understand travel as our ancestors did: our world is too open, relativistic, secular, demystified,” we can strive to tolerate the kind of uncertainty, disorientation, and discomfort that can produce an enlargement of our sense of ourselves. Anxiety, the writers claim, “is part of any person’s quest to find the parameters of life’s possibilities.” “Our wandering is meant to lead back toward ourselves. This is the paradox: we set out on adventures to gain deeper access to ourselves; we travel to transcend our own limitations. Travel should be an art through which our restlessness finds expression.” The authors encourage us to be good guests, to approach travel to foreign places with humility.

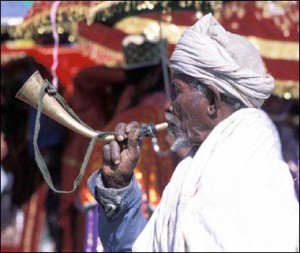

In January 2010, at the ceremony celebrating Timkat, or Epiphany, the most holy day in Ethiopia, the head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church welcomed the small group of tourists who were in the audience of tens of thousands. He said in his sermon, delivered in Amharic and then in English, that there are many ways to spend one’s money, but he applauded our using it to travel so far to share his country’s important ceremony and to learn the essential lesson that people are the same all over the world. I don’t know how to judge our performance as guests, but he was certainly a remarkable host.

In January 2010, at the ceremony celebrating Timkat, or Epiphany, the most holy day in Ethiopia, the head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church welcomed the small group of tourists who were in the audience of tens of thousands. He said in his sermon, delivered in Amharic and then in English, that there are many ways to spend one’s money, but he applauded our using it to travel so far to share his country’s important ceremony and to learn the essential lesson that people are the same all over the world. I don’t know how to judge our performance as guests, but he was certainly a remarkable host.

share

site feed

site feed