- Attached to the essay "The Bugs and Us"

Differing views on parental anxiety

Posted July 21, 2011 12:20 am

For a fascinating food fight about who is most responsible for fomenting parental guilt see Lisa Belkin in the NY Times blog, Motherlode, where she takes up Erica Jong’s Wall Street Journal critique of “new” parenting trends, Mother Madness.

For a sane, measured guide to being good parents there is Benjamin Spock’s breakthrough, Baby and Child Care manual of 1945. “Trust Yourself” is the reassuring title of the book’s preamble. Research shows, Spock writes, that “what good mothers and fathers instinctively feel like doing for their babies is usually best after all. Furthermore, all parents do their best job when they have a natural, easy confidence in themselves.” Spock’s advice, however appealing, has an essential flaw. How can we know we are among those good parents who should trust their instincts? We could be rigid, doctrinaires whose self-confidence is misplaced and be the last to know.  The conundrum calls to mind that of Chuang Tzu, the 3rdcentury BC Chinese philosopher: “I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly dreaming I am a man.”

The conundrum calls to mind that of Chuang Tzu, the 3rdcentury BC Chinese philosopher: “I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly dreaming I am a man.”

Judith Viorst, the children’s book author and poet of our advancing decades, points out, in Necessary Losses, that “human beings have always been raised by fallible human beings.” Our parenting will inevitably be imperfect. “All we need is to be good enough.”

Transmission of information through the generations is now being explored on a cellular level. Soon we will be able to worry, if we are so inclined, about the way our actions (or at least what we eat) will affect our children through our genes. The field of epigenetics, the study of inherited traits not based on DNA information, is only about a decade away from being able to trace how dietary and other behavioral changes are carried genetically and affect our progenies health. The possibilities for parental guilt may expand exponentially.

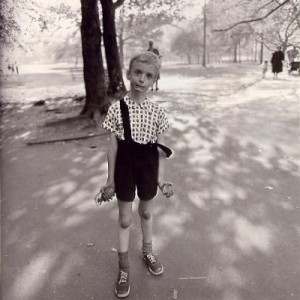

Photo source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Child_with_Toy_Hand_Grenade_in_Central_Park

topics: family

share

site feed

site feed